The Museum of Modern Art in New York has staged an ambitious new exhibition titled The Century of the Child: Growing by Design (1900-2000). The exhibition is a survey of the impact of design upon children throughout the 20th century.

The year 2008 marked the first time in history that more than half of the world’s population lived in cities and towns rather than in the rural countryside. Though this incredible population shift passed us by with little remark, the design world has worked for years to adapt to our new urban environment, particularly with regards to the impact on children. The urbanization and industrialization of the 20th century wrought incredible change on society, both positive and negative; mass production, World War I, World War II, the boom years, the Cold War. Through it all, society began thinking about its children through design.

In 1900 Swedish design reformer and social theorist Ellen Key wrote her seminal treatise called Century of the Child, in which she predicted the change to come. The previous century had not been kind to children; industrialization in England, for example, exploited poor children as a cheap source of labor. Governments lacked even the most basic social security net for their youngest and most vulnerable. Goods and services virtually ignored the existence of children. Parents raised children to be neither seen nor heard.

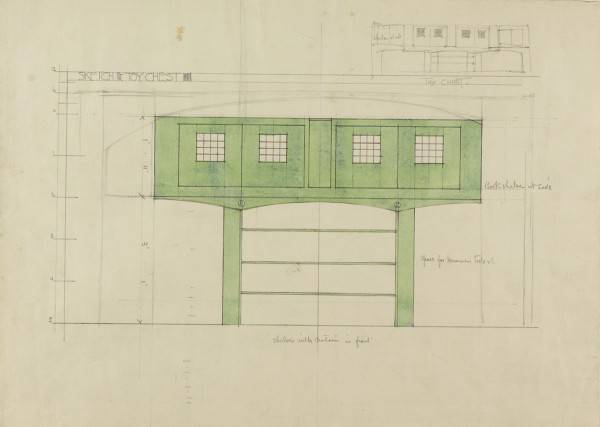

At the turn of the 20th century, things began to change. New Art, an amalgam of the Arts and Crafts movement and Art Nouveau, merged with the Kindergarten movement to mandate a prescribed number of years wherein children could draw, dream, and learn, protected by law from demand for cheap labor. Designers encouraged this movement early on by creating spaces for children to play, such as Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s design for a toy cupboard pictured below.

The horrors of World War I, with its mechanized and systematized traumas, drove designers to contemplate how to save society from another such breakdown. Children, the “citizens of the future”, were seen as the answer. Creative environments were conceived in an effort to allow children to retain the innocence which designers hoped would better society. Toys, playgrounds and children’s books abounded, and mass production meant more children were afforded access to such designs, including the Skippy-Racer, pictured below.

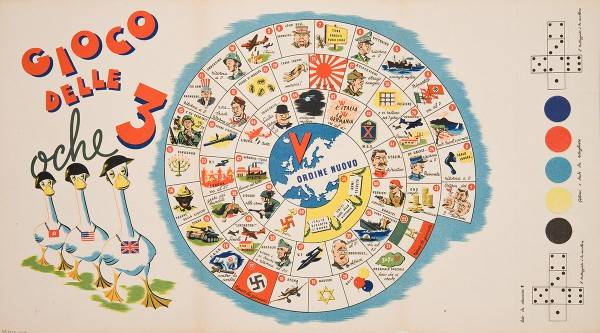

Unfortunately, these hopeful ambitions for children to save the world were not enough to stave off the explosion of socio-political tensions which led to the outbreak of World War II. Suddenly, designers were being drafted to create military uniforms and propaganda showing children as the troops of the future. Even board games were designed to incorporate political messages and notions of victorious war. The game Gioco delle 3 oche pictured below was given to children in wartime Italy; it depicts enemies as silly geese ready for slaughter.

It was not until the dust had settled after World War II that designers revisited the possibility of design as an agent of change and political transcendence. Designers, manufacturers, educators and child psychologists created international coalitions to develop “good toys”. Safe, nonviolent toys re-imagined the place of children in post-war cities around the world. As schools went up all over the world, designers like Jean Prouvé responded with practical but elegant designs, such as the school desk pictured below.

As children’s spaces like schools and playgrounds grew to represent larger parts in the design of cities, the space of children in the commercial market grew as well. Major manufacturers grasped the significance of the untapped market represented by children, and began designing and marketing goods specifically for children. The tin toy Ford cars pictured below engendered lucrative feelings of brand loyalty. Retail consultant Paco Underhill remarked on the phenomenon, saying; “You no longer need to stay clear of the global marketplace just because you’re three-and-a-half feet tall, have no income to speak of and are not permitted to cross the street without Mom. You’re an economic force, now and in the future, and that’s what counts.”

Children now control a significant interest in the markets and design of prosperous cities. However, as we move forward we must embrace the capacity of design to help children where inequalities persist. Though there remains much work ahead, the designer Sugata Mitra has demonstrated how simple designs can effect change. Mitra’s Hole-in-the-Wall Learning Stations provide children in urban slums and rural locations with computer access through simple outdoor designs encasing PCs in durable materials. Children gather at these stations, taking turns playing and learning valuable skills to enrich their potential. We cannot predict the future, but we can try our best to design it.

Century of the Child: Growing by Design (1900-2000) will be on display at the MoMA until November 5. For more information, visit www.moma.org.