Furniture design can be a very complex exercise featuring the problems of engineering and verification that production of a large number of pieces ensues: and the results are often perfect and dramatic. Materials are understood and interpreted, strains forecast and allowed for.

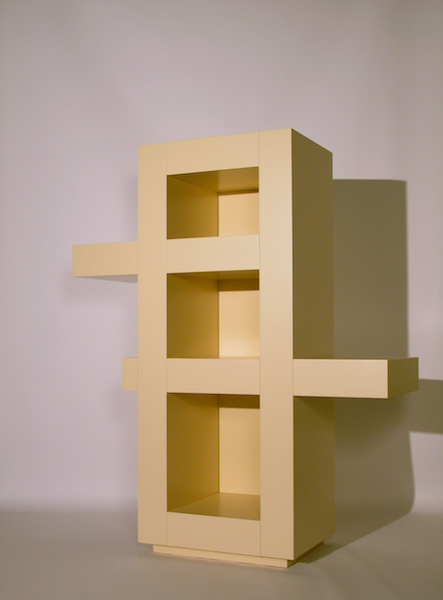

Photo courtesy of Sergio Mannino

But for over a century or so, there has also been the practice, often exercised by a single person, of designing and making furniture that obeys other criteria and has other aims, i.e. the description of a fantastic world, the desire of a thinker to express himself with a design, and then the actual construction of allegories, of ‘physicalism’ diagrams of thought.

Some architects do this because they have discovered that the creation of a piece of furniture can aid them in working out an architectural plan as well as illustrate many things: their time, their existence, their love, desires and wishes. When one considers architecture, on whatever scale, when the models are prepared in reduced size, the checks are often uncertain…

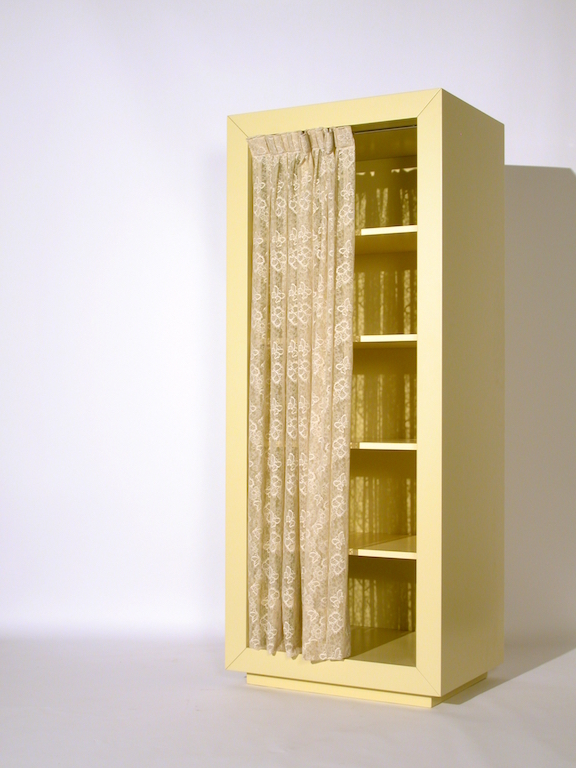

Photo courtesy of Sergio Mannino

In furniture, the design exercise is less frustrating: one can use drawings or models, but (and furniture is unique in this in the world of design) the models must be life-size, not reduced, and the materials used have to be the actual ones planned! It means working on the project and not being bogged down on a silly 1:100 scale (if you’re lucky).

This was a great discovery for those in my generation, like Archizoom, Ufo, Superstudio, and of course myself. Being faced by the full-size results of your design phase, in the actual materials, and in just a short space of time (compared to the years that architectural plans require, and when the building is finally completed, you have already moved on, you are after), producing the design, tackling it, and seeing it face to face is a thrilling experience. This is permitted to visual artists like actors and set designers, but to architects no. Thus, the production of furniture becomes an important aspect of the architect’s externalization of self and the organization of spaces. And seeing that you are right at the start, your own vision of the world flows into these allegories. The item of furniture becomes a vehicle or a tool that allows you to externalize and face up to yourself, it becomes a place of dreams, the fantastic and the visionary. All this is accompanied by writings, drawings, models, prototypes and paraphernalia.

Photo courtesy of Sergio Mannino

Someone is responsible for all this. Who was it that began to bring back to the design process from the traditional architecture menu the ingredients that had been expelled from it during the 1930s? Right after the Second World War, Ettore Sottsass began to follow an entirely independent route in the world of design in which, in his hands, the functionalist experience seemed to lose strength and be replaced by materials, color and ornamentation. These are the spices that were removed from the menu when, in the 1920s, at the risk of bulimia, architecture decided to slim down and limit itself to the simplified diet of pure geometry. Ettore understood that for him such a diet would risk anorexia, so he slowly brought back to his own table materials, color and ornamentation to re-establish a balance.

He did so in his production of furniture, glassworks and ceramics, often at his own expense and often ‘…impossible to produce, impossible to transport, impossible to make them pay…’. Andrea, Lapo, myself, Cristiano, Adolfo and then Alessandro, Gaetano and Riccardo* understood by examining his works that, yes, design was not just the mirror of a rational world but could describe so many other things, ourselves, desires, the love of love, emotions, irony and the crossing of barriers. The design had to tell a story and describe ourselves. That’s a hell of a task. It was stirring, radical stuff. Global Tools, Alchimia, Memphis: one after another these were where my first students went, and then those of Adolfo, like Michele (De Lucchi), and then those of Buti, like Giovannoni and Venturini and today Mannino.

Photo courtesy of Sergio Mannino

For years, students and young graduates flocked from Florence to Milan, and of those who were seduced by this climate, Sergio remains the one who interprets this world in the most orthodox manner. In his university thesis he was already searching out Ettore, and with him learned to design small, marvelous houses halfway between nature and spatial organizations that were simple, intense and well-balanced. His furniture also had the desire to capture alphabets and thoughts, so as to describe and use them to make statements through their construction, defining consistency colors transparency.

Photo courtesy of Sergio Mannino

In my opinion, Ettore’s best pieces are produced when he lets himself go, and his subject matter faces you square on, almost two-dimensional, with the almost mechanical addition of depth. His designs make the statement about the possibility of existence, alone, in a room.

Sergio understood the lesson and these works of his describe the routes he has taken within himself and within us.